View this email in your browser

“…it is increasingly clear that water scarcity and insecurity are not so much related to the absolute availability of fresh and clean water, but rather are expressions of how water, and water services, are unequally distributed among societal groups. Unequal water distribution and exposure to contaminated water, flooding and failed water projects often reveal elite capture of the state and related biased policies and corrupt practices. In other words, the so- called “water crisis” is less a consequence of generalized scarcity than a manifestation of uneven power geometries (UNDP, 2006).”

- From the introduction to Water Justice, Boelens, Rutgerd & Perreault, Tom & Vos, Jeroen (2018) via Research Gate.

The Weight of Water

When I begin preparing this newsletter, I never know in advance what the outcome will be. I have no schedule of topics or themes. I prefer to leave myself open to what seems of particular relevance. There are certain umbrella topics that remain on my radar but I’ve also found that current events frequently demand a dedicated response. That is the case now. I cannot stop thinking about water - the fact that it is 100% essential to our existence on this planet and that humans seem bent on directly or indirectly limiting, harming or wasting a resource on which we all depend.

I don’t get it.

So part of this newsletter is asking us to stretch our brains and connect the dots between the drastic effects of climate change on the world’s water supplies, manufactured water scarcity enabled by those seeking to privatise public sources, and the alarming levels of pollution to waterways around the globe. (I’m thinking particularly of the raw sewage flowing into the UK’s beach areas that was in the news this and last summer.)

There were two recent events which put this topic on my immediate agenda. The dramatic flooding in Pakistan and stories about Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, having to close schools indefinitely due to a city-wide lack of clean drinking water. Attached to both events was very selective coverage by mainstream North American media. While I noticed several shocking video clips of whole buildings being swept away in the massive deluges coursing through the Balochistan and Sindh provinces of Pakistan, I was not seeing widespread sharing of disaster relief efforts that one would expect in response to such a tremendous humanitarian disaster with over 1100 deaths and 30 million displaced people. I wondered why.

Of course, the answer is complex. It has to do with the limits of my own filter bubble and the news sources to which I typically subscribe. The fact that Pakistan is a majority Muslim country often in fraught relationship with the US and other Western states may also play a role.

This article in The Guardian describes the extent of the havoc wrought.

I found this database of verified relief efforts compiled by researcher Zoya Rehman which is labeled by region and specific requests (material, cash or both).

Water access to Jackson residents was curtailed due to severe damage of a crumbling water treatment plant after a recent flood. But Jackson’s water infrastructure crisis has been years in the making, following a pattern of disinvestment in the city where 84% of residents are Black. If you are reminded of the heavily contaminated drinking water in Flint, Michigan, that’s not a coincidence.

This brief TikTok video by AJ+ offers an accessible overview of the crisis and its multifaceted origins (white flight, disinvestment, deferred maintenance, privatised repair service).

Local journalism at Mississippi Free Press played a huge role in putting this crisis on the radar of national media. Their research and coverage over years has formed the backbone of wider reporting. An important reminder of why we need to support local journalism.

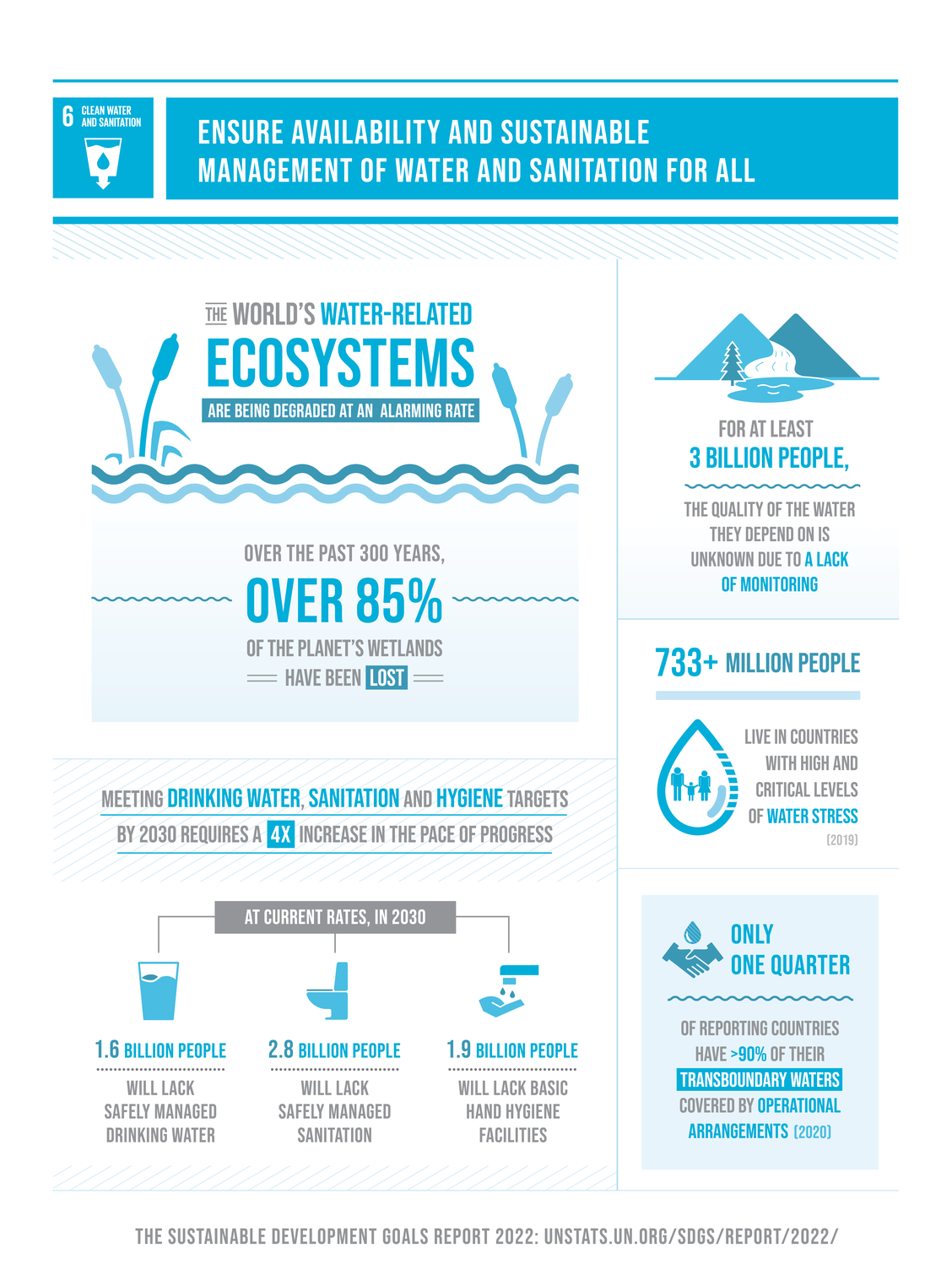

From the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals website, here’s an overview of what we face on a global scale:

Recognizing the intersections between environmental degradation, racism and classism needs to be a central component of our understanding of equity and justice, particularly when we consider our attempts to protect the planet. I just finished reading Linda Villarosa’s book, Under The Skin, which looks specifically at the toll of racism on American lives. Her chapter on environmental racism was eye-opening and gut wrenching.

Thinking about our fresh school year, I want to bring two more things to your attention:

As it is September, before you talk with students (or anyone, frankly) about 9/11, please, please read this article by educator and researcher, Dr. Sawsan Jaber: “The Miseducation of Americans on Arab and Muslim Identities.”

Consider, too, this deeply helpful article by international school researcher and expert, Dr. Danau Tanu, “Are International School Parents Racist?” - A provocative title for an urgently needed analysis.

Classrooms of Ancestors

One of the things that struck me as I tried to pull my thoughts together on these related, far-reaching topics: water and climate disaster, political neglect and water scarcity, profit motives and water pollution; I’m asking myself, how do we educate for generations? How do we build consciousness for futures that extend beyond our students’ lifetimes?

If we consider the specific challenges presented here, many of the causes are rooted in negotiating short term advantages (profits, political power) over the prospects of long term sustainability. Capitalism and neoliberalism live off this framing of everything. Our education systems are not immune to these dynamics. Rather, in many ways we are forced and expected to answer to them. We shuttle students through our schools with messages about how short term gains (good grades, college completion) will secure their long term futures. Additionally, we have strong political forces engaging in a sort of educational deforestation in which the goal is to weed out the difficult social stuff (like accurate History) that provides perspective on the conundrum of human existence. Let’s be clear: Education consistently faces the threat of erosion.

What we don’t spend nearly enough time and energy on is stepping back to consider the long view; the way our ancestors dreamt, the ways we must dream to make a future possible for those who will come long, long after our children and their children. That’s a big ask, I know.

And it’s September, when my hopes and ambition might be at their strongest. So dream with me, if you choose. Welcome aboard!

Be well, friends!

Sherri

image credit: StockSnap via Pixabay